Deep Dives on State Revolving Fund Policies

The United States faces widespread water infrastructure challenges, and addressing these challenges requires the coordination, financial support, expertise, and effective policies of local, state, and federal government. Functioning drinking water, stormwater, and wastewater infrastructure delivers clean water to our homes, safely treats and disposes of waste, and mitigates the impacts of severe weather and reduces the amount of pollution in our waterways. The Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (CWSRF and DWSRF) represent the largest sources of federal funding for water infrastructure – states receive this federal funding, provide a state match, and develop policies and procedures to disburse SRF dollars.

In the American Society of Civil Engineer’s 2025 “Report Card for America’s Infrastructure,” drinking water infrastructure is rated as a “C-,” stormwater infrastructure received a “D” grade, and wastewater infrastructure a “D+.” Clearly, we have room for improvement. Our current federal investment levels leave enormous gaps in need and makes it even more imperative for states to structure their SRF programs to direct funding to communities and projects that alleviate pressing concerns around public health, resiliency, and water affordability.

Below, explore three different states’ approaches to:

- Ensure public participation and provide transparent procedural practices

- Develop and implement equitable “disadvantaged community” (DAC) definition and project priority ranking criteria to direct funding, and better financial terms, to communities with greatest need, and

- Enhance the ability of applicants to implement green infrastructure/projects that focus on nature-based solutions.

Lessons from Wisconsin: Redefining “Disadvantaged Community” and Shifting Scoring Criteria

Lessons from Wisconsin: Redefining “Disadvantaged Community” and Shifting Scoring Criteria

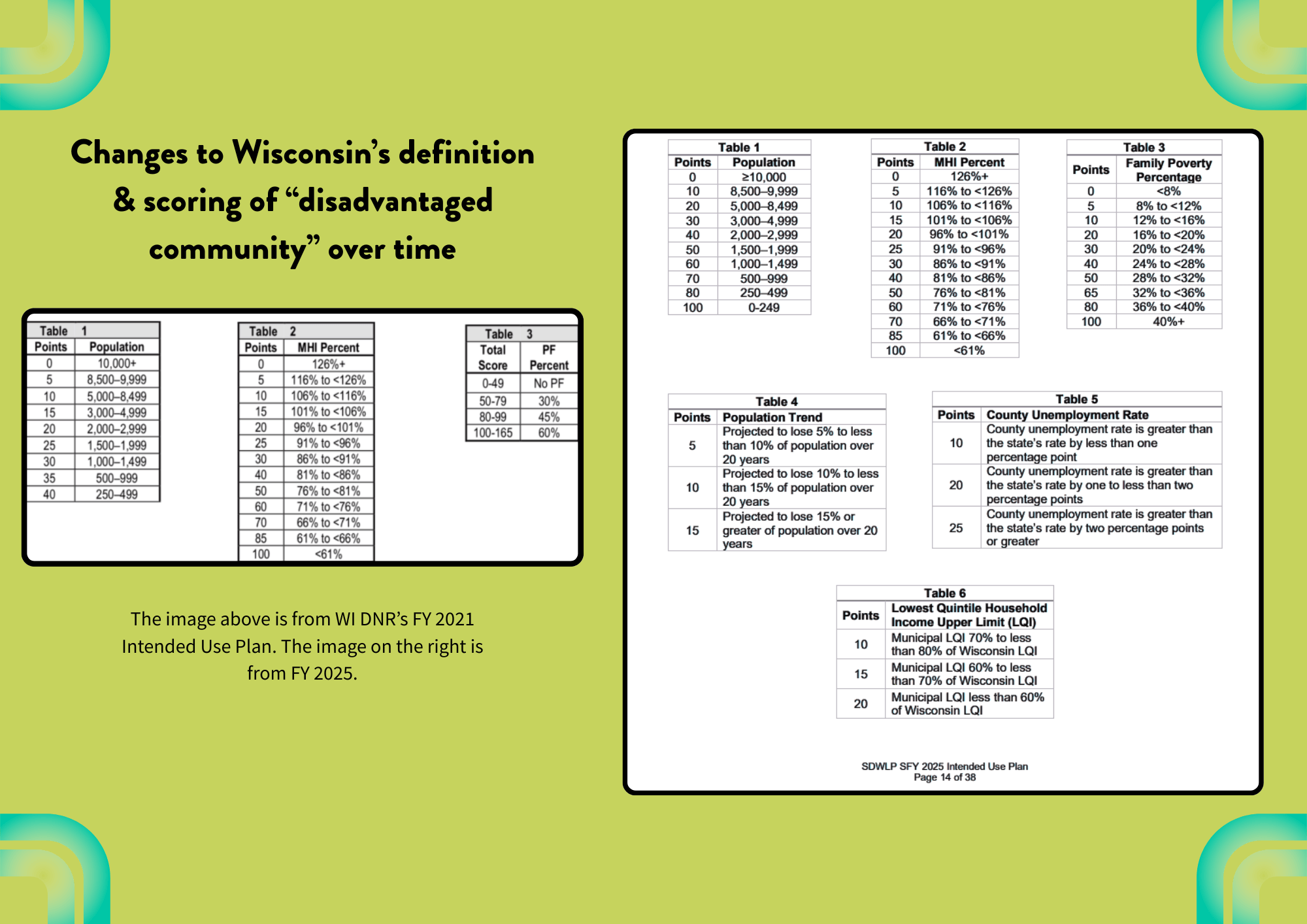

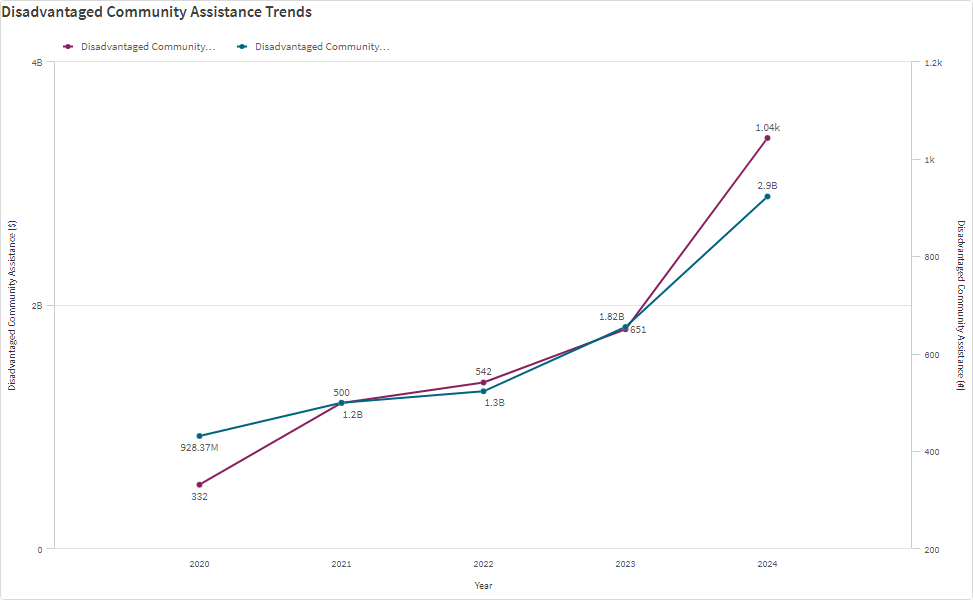

After the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) was passed at the federal level, the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Water issued guidance to states, encouraging them to review and revise their disadvantaged community (DAC) definition/affordability criteria, as well as how projects are scored and ranked, with the aim of directing more principal forgiveness (a portion of a loan that does not have to be repaid) to DACs. Many states began to consider adjusting and refining their DAC definition and scoring criteria, but Wisconsin had actually already started this process. The state’s older DAC definition only considered population, with smaller populations receiving more points, and median household income (MHI) of a municipality, with a project scoring points that were broken up into four tiers to qualify for principal forgiveness.

Key Policy Language

The new DAC factors shown in tables 1-6 are tallied to indicate how much principal forgiveness a project is eligible for.

- 0–59 points, no principal forgiveness,

- 60–69 10%

- 70–79 15%

- 80–94 20%

- 95–109 25%

- 110–124 30%

- 125–139 35%

- 140–154 40%

- 155–169 45%

- 70–184 50%

- 185–199 55%

- 200–249 60%

- 250–360 65%

In the FY 2025 IUP, there is further specification of how principal forgiveness will be distributed, including “No general PF-only awards – As a revolving loan program, fiscal prudence dictates that the SDWLP only award PF for projects for which loan funds are also awarded. This results in a continuation of fund integrity while providing some funding in the form of PF, helping disadvantaged municipalities offset some costs of their infrastructure improvements. This restriction does not apply to lead service line replacement projects.”

Advocacy and Implementation Efforts

Several organizations in Wisconsin have been committed to improving the state’s SRF programs for many years. These include Milwaukee Water Commons and Coalition on Lead Emergency (COLE). Over time, advocates have built strong relationships with the state SRF staff, as well as local utilities, to effectively identify barriers and problems and generate solutions, including but not limited to the state’s DAC definition and project prioritization.

The SRF State Advocates Forum maintains a library of IUP comments that advocates submit. Explore the multitude of Wisconsin public comments here.

Milwaukee Water Commons IUP comments for state FY 2025 express appreciation for Wisconsin DNR’s efforts, and also pushes them to invest time and energy to hear from disadvantaged communities, “As the WDNR considers these opportunities to create a more accessible Intended Use Plan process, we would continue to encourage that there is a priority placed on engaging disadvantaged communities in the review of the policies guiding the SDWLP. Making this program more accessible will encourage local advocates, beyond engineering firms, municipalities and other conventional partners to become more involved in shaping the applications for drinking water infrastructure projects in their communities. This effort could also help water systems communicate more transparently with their local partners and rate payers about project planning and priorities for leveraging state/federal funding. This is an opportunity to eliminate barriers that prevent more representative community engagement, and ensure that policies and procedures result in fair treatment and equitable access.”

Lessons from Ohio: Directing SRF $ to Nature-Based Solutions & Green Infrastructure

Lessons from Ohio: Directing SRF $ to Nature-Based Solutions & Green Infrastructure

In a 2024 report, the Brookings Institution examined all 50 states and Puerto Rico’s Intended Use Plans (IUPs), and found that for the CWSRF, 65% of states’ IUPs explicitly mention “green projects” in short- and long-term goals and 37% of DWSRF IUPs across states also include “green projects” within their programmatic goals. Relatedly, a 2024 audit by the Office of Inspector General found that only “49 percent of states included climate adaptation or related resilience efforts in their 2022 IUPs.” While Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA) and Ohio Water Development Authority, the two state agencies that administer the CWSRF and DWSRF programs in Ohio, do not specify “green projects” in their IUP goals, Ohio is considered a leading state when it comes to directing SRF dollars to projects that include green stormwater infrastructure, nature-based solutions, and climate resilience components.

In 2000, Ohio’s creation of the Water Resources Restoration Sponsor Program (WRRSP) as part of the Water Pollution Control Loan Fund ((WPCLF) Ohio’s name for their Clean Water SRF program), made it the first state to develop a sponsorship program for non-point source projects.

What is a Sponsorship Lending Program?

Non-point source projects often lack a revenue stream, which makes taking out a CWSRF loan untenable, because there is no way to pay the loan back. A sponsorship lending program addresses this issue by connecting a traditional publicly owned treatment works project with a “nontraditional” one. As the traditional project’s loan is repaid, a portion of those loan repayments funds the non-point source project. In Ohio, the state uses a small portion of repaid WPCLF funds for projects that qualify for the Water Resources Restoration Sponsor Program. A municipality or other eligible applicant applies for funding as a “sponsor” in coordination with an “implementor” entity to identify, plan, design, and construct WRRSP projects. The sponsor is incentivized to participate through lower interest rates for the traditional project.

Key Policy Language

The Water Pollution Control Loan Fund is administered under Section 6111.036 of the Ohio Revised Code. Rules that support the implementation of parts of the WPCLF can be found at Ohio Administrative Code 3745-150. The state legislation gives Ohio EPA the authority to establish innovative programs like the WRRSP. Annual Intended Use Plans, which in Ohio are called “Program Management Plans,” detail the structure of the program and how projects are selected.

In program year 2024, the Program Management Plan states, “The intent of the WRRSP is to address non-point source projects (NPS) that have been an historically under assisted category of water resource needs in SRF programs. While significant progress has been made in reducing the impact of discharges from municipal wastewater treatment plants on water quality, in large part due to financial assistance provided through the WPCLF, the best available data indicates that impacts from nonpoint source runoff, habitat degradation, and watershed disturbances continue to impede over-all rates of water resource improvements and threaten much of the progress that has been made. The goal of the WRRSP is to counter the loss of ecological function and biological diversity that jeopardize the health of Ohio’s water resources. The WRRSP helps achieve this goal by providing funds, through WPCLF loans, to finance the implementation of projects that protect or restore water resources.”

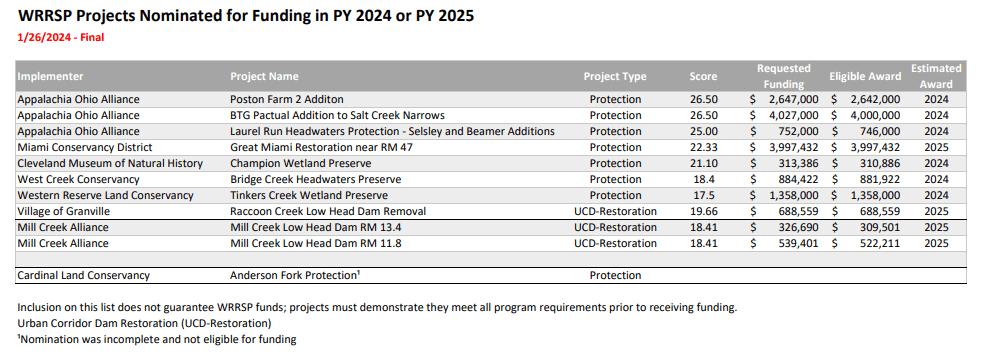

Ranking Projects

The Program Management Plan further outlines how projects are ranked and selected.

“WRRSP projects will be ranked in two categories: the Water Resource Protection Category and the Water Resource Restoration Category.

- Water Resource Protection Category – This category consists of projects that protect the long-term protection of high-quality water resources.

- Water Resource Restoration Category – This category consists of projects that involve addressing impairments to the water resource and their long-term protection.”

“…WRRSP projects are evaluated based on the quality of the existing resource, effectiveness of action of the proposed project, proposed ecological lift of restoration activities, cost effectiveness of the project, and implementability and readiness to proceed of the proposed projects. Other factors may also be evaluated to determine project rankings.”

Advocacy and Implementation Efforts

In the 25 years since the WRRSP’s establishment, dozens of projects across the state have been completed. The implementors and sponsors of these projects work together to protect and restore water resources. The program has adapted over time to emerging needs – for example, in 2020, Ohio EPA added a new subcategory to address dam removal in urban stream corridors.

Read Ohio’s Water Resources Restoration Sponsorship Program: A 20-Year Success, by Environmental Policy Innovation Center, for an overview of the enabling conditions that set Ohio’s program up for success.