Changing Narratives in Milwaukee with Water Infrastructure Dollars

We often talk about: what is the wraparound community benefit of these programs? And how is it changing that narrative of segregation in Milwaukee?”

-Joe Fitzgerald, Policy and Advocacy Manager with Milwaukee Water Commons

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has global recognition as a water-centric city, however depending on where you live, your relationship with water may be entirely different. Milwaukee is recognized as the fifth-most segregated city in America, and for many families living on the City’s north and south side, safe drinking water and flooding concerns are a big part of their water story. Community organization Milwaukee Water Commons (MWC) has been working to leverage federal infrastructure funding to address environmental hazards and barriers to employment experienced in underserved Milwaukee neighborhoods by organizing using four frameworks: environmental justice, collective action, the commons, and community engagement.

“When [MWC] started, the organization focused on connecting with residents around Milwaukee to understand what it would mean to them to live in a true water centric city,” shared Joe Fitzgerald, Policy and Advocacy Manager with MWC. “There had been a lot of conversations between government institutions, academia, and businesses in Milwaukee about that question, but hardly any conversations with residents, and especially with any intentionality to bridge the gaps perpetuated by segregation in our city.”

From its founding in 2013, MWC has sought representative engagement of Milwaukee residents on decisions about water in Milwaukee communities – as well as at the state and federal levels. These days, as is true for so many across the national network of river, justice, and water advocates, that means figuring out complex federal funding programs, and ensuring the dollars made available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) advance equity. Longtime River Network members, and frequent River Rally participants, panelists, and presenters, we are honored to be one of MWC’s many collaborators in this space, including through their participation in the SRF State Advocates Forum. State Revolving Funds (SRFs) are one of the primary pathways through which water infrastructure dollars are flowing.

River Network’s national focus is on education and community building – through the Forum, our SRF Advocacy Toolkit, SRF Online Learning Series, other federal funding resources, and by sharing stories like MWC’s. They’re one powerful example among many groups on the ground in their communities and states, ensuring these dollars are spent equitably. For MWC, they’re also leveraging their state’s SRF program to foster more equitable and just policies that change two dominant narratives: the narrative of segregation and injustice, and the narrative of water utilities and the communities.

Changing the Narrative of Segregation and Injustice

The city of Milwaukee centers its connections to water on their city website proclaiming, “with three rivers and a Great Lake, water plays a key role in the city’s history, identity, and economy.” Today, the city’s primary water concerns center on safe drinking water and urban flooding, environmental hazards that disproportionately impact lower income Black and Brown communities in Milwaukee.

Milwaukee’s history includes redlining, the effects of which still contribute to disparities in access to employment opportunities, educational attainment, income and poverty, health outcomes, and incarceration by race. Lines of segregation in Milwaukee also limit access to green spaces, waterways, and a healthy environment.

Lead service lines (LSLs), once totalling around 70,000 throughout the city’s water system, are down today to around 65,000 since the city’s lead service line replacement program started in 2017. This number still leaves a large portion of the population exposed to the dangers of lead infrastructure, and contributes to a higher frequency of lead poisoning cases in lower income neighborhoods on Milwaukee’s north and south sides.

Mayor Cavalier Johnson and Senator Tammy Baldwin join Milwaukee Water Works at the site of a lead service line replacement in Milwaukee to announce the launch of the City’s Lead Service Line Equity Prioritization Plan with an infusion of federal funding through the SRF program. Photo courtesy MWC.

The City’s position on Lake Michigan and the confluence of three rivers also makes some neighborhoods in historic wetlands particularly prone to flooding and basement backups during major storms. The Kinnickinnic River watershed, located in the predominantly Latinx neighborhoods on Milwaukee’s southside, is almost 97% impervious surfaces, which Fitzgerald explains makes it “dangerous for folks to be near their local waterway. It’s like a Class 5 rapid on the river during a major rainstorm.”

Another perhaps less obvious factor is Milwaukee’s under-maintained tree canopy and inequitable coverage of tree canopy. Fitzgerald described how, “[Milwaukee] lost a lot of trees to Dutch Elm disease and are also losing trees to the Emerald Ash Borer. When there’s a big storm that comes through Milwaukee… due to a lack of funding for maintenance of the trees that do exist, we also have a lot of issues of folks with branches falling on their houses, falling on their cars, trees falling on the street.” Tree cover in a city absorbs significant amounts of stormwater, and without this, flooding issues in Milwaukee are exacerbated. (The City of Milwaukee received an Urban and Community Forestry grant from USDA and USFS to address these interconnected challenges; River Network is honored to be a National Pass-Through Partner in the program as well.)

Residents in Milwaukee’s Sherman Park Neighborhood work with Milwaukee Water Commons and its partners to restore neighborhood tree canopy found in open public spaces. (Photo Credit – Pat Robinson.)

MWC’s water infrastructure efforts stem directly from these water concerns and their community’s desires to address them. “Our organization’s start in getting involved around water infrastructure came from a call from the community: that they want safe water to drink; that they want clean water to visit in our lakes and rivers; and that they want a safe relationship with water as well,” said Fitzgerald.

These present day desires are driven by a complex and unique history.

The city also saw white flight and suburban sprawl, beginning with racially restrictive covenants as early as 1919, and other policies continuing into the mid-20th century. As a result, and, “because we’re an older, major city… our infrastructure system is generally older than some of the other communities around us in the suburbs and exurbs, and our population is smaller than the infrastructure system was initially built for.”

The bottom line? So much wealth has left the city that Milwaukee’s current residents disproportionately experience poverty and the city has an oversized water system without the rate payer base to address its water infrastructure concerns.

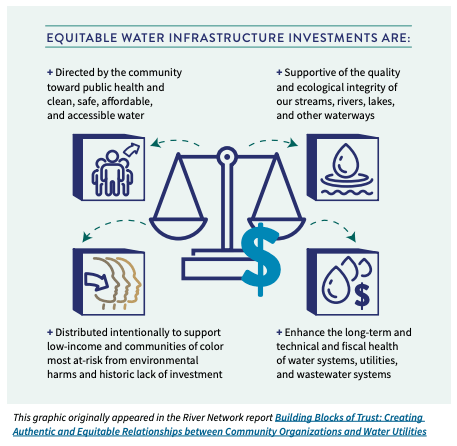

This is where MWC’s SRF advocacy comes in. They recognized this opportunity as a chance to change this long-standing spatial racism and advance their three areas of justice: procedural justice, distributive justice, and restorative justice.

Procedural Justice

Procedural justice calls for inclusion and representative engagement in decision-making, especially prioritizing those who are impacted by the decisions being made.”

-Joe Fitzgerald

Do you know when your state’s Intended Use Plan (IUP) comment period is? “One of the things that we learned was that before the implementation of the BIL there just really weren’t very many comments being received and there wasn’t a lot of communication going on with communities about whether [Wisconsin’s] SRF program was working well or not,” shared Fitzgerald.

Milwaukee Water Commons has advocated for more representative community engagement and active inclusion of stakeholders to inform the policies guiding the SRF program. In addition to convening public comments with local partners, and calling on Wisconsin’s SRF administrators to measure representative community engagement as a metric for success for the review of Intended Use Plans, MWC worked with Clean Wisconsin and the Healing Our Waters Coalition to connect with utilities around the state of Wisconsin to talk more about both the challenges and opportunities presented by the influx of funding through the SRF program, producing the WI Water Infrastructure Financing Memo.

“We’ve also been able to work more, and talk more with [our state SRF administrators] about how [the program runs,” explained Fitzgerald. “Wisconsin does publish its feedback on Intended Use Plans. They do webinars on their IUP policies and application deadlines.” A resulting success of this increased engagement is the use of set-aside funding from BIL to staff up the Wisconsin SRF program administrative team. “They now have a number of staff who are really working to connect with utilities, unpack barriers, and get folks connected to funding that addresses their water infrastructure challenges.” Milwaukee Water Commons also continues to convene a statewide forum focused on Wisconsin’s implementation of the SRF program engaging the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), technical assistance centers, and both utilities and non-profit organizations from around the state working to address water infrastructure challenges. “Water challenges are a statewide issue, and whether you are in an urban or rural community, these federal dollars should be used to ensure that communities facing environmental injustice have access to clean, safe and affordable water.”

Distributive Justice

Distributive justice refers to the equitable distribution of resources and opportunities across communities. This may be in regard to the prioritization of water infrastructure projects, the distribution of funding to address infrastructure needs, or even the distribution of employment opportunities.”

-Joe Fitzgerald

As Milwaukee Water Commons began interacting with Wisconsin’s SRF program, they zoomed out, unpacking what the program looked like across the state. At the time, Wisconsin was scoring community eligibility for principal forgiveness considering the municipality’s median household income and whether the population was under 10,000. This approach assumes that smaller communities with fewer rate payers to draw from may need additional support to invest in infrastructure projects. “This is real,” acknowledged Fitzgerald, “But it does not account for the barriers faced by larger cities that often have older water infrastructure systems, a shrinking population due to white flight and suburban sprawl, and major disparities in wealth and household income.”

The policies needed to change to ensure that BIL funding would truly reach “disadvantaged communities.” Fortunately, coordinated advocacy by Milwaukee Water Commons’ and their partners, such as the Coalition on Lead Emergency and even Milwaukee’s drinking water utility, brought about a big shift after conversations with their State administrators. “We moved to having measurements on population with a more gradual kind of tiering system,” explained Fitzgerald. Median household income was still included, but with additional ranking criteria such as family poverty percentage, population trends, unemployment rates, and lowest quintile household income that would ensure funding reached disadvantaged communities in both large urban areas and small rural communities.

In addition, the state of Wisconsin is now piloting a new approach to applications for lead service line replacement projects, where utilities can apply for projects in specific census blocks of their service area. While it may sound complicated, at the end of the day, this was a narrative change: “we really tried to outline and unpack [what] we mean when we say ‘disadvantaged community’ including more metrics that would be more representative, and capture more of the disparity in communities across the state.” These changes ensure a more equitable distribution of Wisconsin’s SRF dollars.

There’s another developing angle on MWC’s call for distributive justice: equitable workforce development. “We also talk about the distribution of jobs and opportunities to access employment in the [water] sector,” said Fitzgerald. Communities and states are setting a lot of ambitious goals around infrastructure as this federal money rolls out. In tandem, we must ensure there is a workforce in place to get this work done. The city of Milwaukee in particular is a majority minority city, but employment in the water trades – including plumbers and pipefitters – is up to 99% white men. MWC is looking at workforce development as both a challenge and an opportunity for distributive justice. Milwaukee Water Commons helps to facilitate the Milwaukee Water Equity Task Force, a coalition dedicated to building the organizational, policy, and partnership capacity of community organizations, utilities, governmental agencies, philanthropy, policymakers, environmental groups, industry partners, and other stakeholders to chart a new course toward an equitable future. The group is focused locally on mobilizing approaches to equitable workforce development and on influencing the implementation of infrastructure funding to affect the disparities in the sector and create access to living wage employment for under and unemployed residents.

The core questions posed by MWC and community groups around the country are: what does it mean to be getting these major injections of federal funding; what policies or programs need to change to ensure that the outcomes of these investments lead to equitable and just outcomes for our community?

“It’s exciting to see this funding coming in,” said Fitzgerald, “but there’s also a lot of work that needs to be done to make sure that money ends up staying in Milwaukee, supporting local businesses, creating pathways to employment for folks who are unemployed, and diversifying the sector to create opportunities for women and people of color who just aren’t a part of the water sector right now.”

Restorative Justice

Since there is such a deep level of hyper-segregation [in Milwaukee,] it’s also important for us to be thinking about how investments in water infrastructure can mitigate some of that harm. Restorative justice refers to actions that intentionally interrupt past and current harm and empower communities.”

-Joe Fitzgerald

In addition to MWC’s advocacy on principal forgiveness scoring criteria described above, they also pushed for a change in the narrative around the criteria’s geographic scale, to better identify areas of need, more intentionally focusing on communities where there has been long-term exclusion from investment.

“If you take [the principal scoring criteria] metrics for the whole city of Milwaukee versus for a neighborhood in Milwaukee where there’s a high density of lead service lines, it could come up with entirely different outcomes,” said Fitzgerald. MWC successfully advocated for using the census block level when prioritizing projects, an approach that is being piloted with the lead service line removal program currently, and which Fitzgerald says “opened up a lot more access.”

This state level advocacy happened in tandem with coordination on the development of the city of Milwaukee’s lead service line prioritization plan. “There’s a weighted scoring where the city now has moved from only replacing pipes as they break, or during planned projects or for childcare facilities.’ They will still do that, but the prioritization plan will increase the number of pipes being replaced each year targeting neighborhoods that have been identified as the most disadvantaged,” said Fitzgerald. The City of Milwaukee’s lead service line prioritization plan also passed with zero cost share for residents participating in the program.

Looking ahead at restorative justice work, a major MWC goal is to see more coordination with Tribes on accessing water infrastructure funds. “There’s a whole set-aside program [for Tribes], but Tribes are eligible to apply and be awarded through the State programs as well, and we just haven’t seen that [happen] historically, in Wisconsin,” explained Fitzgerald. MWC will be looking for opportunities for coordination and outreach between the state of Wisconsin and tribal governments, to see those set aside programs implemented to address the infrastructure challenges being felt on tribal lands across the state.

Changing the Narrative Between Utilities and Communities

A common call River Network often hears from members and other community groups is a desire to build stronger and more productive relationships with their local water utilities. MWC has felt this pull too, and so when water infrastructure dollars began flowing, they saw another opportunity. In most cases, drinking water and wastewater utilities are the entities that apply for SRF funding. This means that to have influence and ensure equitable outcomes, community groups must work with their utility partners. “This investment that’s happening right now around water infrastructure is being framed as a once in a generation opportunity. So, it’s one that we really need to work together on ensuring that we’re approaching things differently, seeing not just the investment, but also the change in those systems that those dollars are [flowing through],” shared Fitzgerald. “The reality is that that needs to be happening in partnership with our utilities and government institutions and other folks who are all a part of ensuring that the implementation of this [SRF] program is successful. This work cannot effectively be done in silos, our institutions cannot do it without community leaders and vice versa.”

When it comes to this “one in a generation” framing, though, Fitzgerald and many others in the water sector, including River Network, take issue. “I get frustrated by that phrase in general… because it shouldn’t be. But also, looking back, it also means there’s been decades when utilities and community groups have been trying to address these huge issues without the [necessary] resources, which is what has led in some cases to conflict.” This historical moment presents an opportunity to change that narrative and come together to get ahead of that potential for conflict and get down to the work at hand: addressing critical water and environmental justice issues.

After BIL passed, MWC made a big push to connect with utilities from around the state of Wisconsin. This push was both because of the reasons above, and to get out ahead of yet another persistent narrative: the urban-rural divide and the impression that communities are in competition with each other to address environmental justice issues.

If you are a community leader, a utility leader, somebody in [an SRF] administration office, or working at the EPA, everyone in one of those positions should have the mission of addressing environmental justice concerns for communities that don’t have access to clean drinking water and don’t have access to safe water spaces.”

-Joe Fitzgerald

Breaking down narratives of divisiveness has been a big emphasis of MWC’s SRF advocacy: trying to change the way that we’re working and encouraging everyone involved to be hard on the problem, not necessarily on the people. Establishing relationships with utilities first was key to MWC’s advocacy success, and their “utility partners have been big assets in breaking the narrative on conflict,” shared Fitzgerald. “We’ve been able to develop some really strong relationships with our utility leaders. There’s still always some ‘storming and norming’ and figuring out how to manage power dynamics.” MWC didn’t back down from the challenge, unpacking institutional processes and inviting utility partners to think about the ways that hierarchy, racism, and sexism show up in institutions.

Success Through Coalition

A lot of those victories came in coalition. I’m not saying it was all Milwaukee Water Commons that made any of this happen. It came through collective action working with utilities and coordination with non profits and the community to [achieve success].”

-Joe Fitzgerald

Utilities are just one partner for MWC in their SRF advocacy work. Regionally, they work with the Healing Our Waters Great Lakes (HOW) Coalition; at the state and local levels they often partner with Clean Wisconsin and the Coalition on Lead Emergency (COLE). They’re also a member of the Water Equity and Climate Resilience Caucus (as is River Network), and are grateful for the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC)’s countless resources that help groups unpack SRFs. US Water Alliance is another close partner, supporting MWC’s work with utility partners.

Milwaukee Water Commons staff and board participate in the 2023 Healing Our Waters Great Lakes Conference in Cleveland Ohio. Photo courtesy MWC.

Fitzgerald is also an active member in the SRF State Advocates Forum, a group led by River Network, EPIC, Alliance for the Great Lakes, and PolicyLink, where advocates from all across the country share and learn. “[The Forum] has been really important, especially as [BIL] was unfolding, for us and for other partners to have a space to really unpack as nonprofits, ‘what is the SRF program? How does it operate?’ To have that kind of dialogue between states, so when you’re running up against a wall, you have somewhere to recharge and speak with folks and know that that fight can happen.”

Fitzgerald also noted the importance of hearing from others’ successes to be able to bring those examples back to Milwaukee and say, for example, ‘this is what’s going on in Newark.’ “Having that kind of community has been big for these local fights.” The space also helps groups decide where and how to push for change. “It’s great just having a place to unpack what’s a federal fight, what’s at the state level, what’s a local fight? And learning how to lean in, especially as a community based organization.”

Here, Fitzgerald paused. “This goes back to where our conversation started, with Milwaukee Water Commons’ origins. We began with ‘we shouldn’t be drinking water out of lead pipes,’ to now have successfully advocated in all of these arenas. That takes a lot of partnership and coordination; having these spaces [like the Forum] is really important.”

For more on how River Network and others work in coalition, read this September 2023 article from River Network staff.

What Narratives Can You Change?

However you feel about recent federal water infrastructure investments being framed as “once in a generation,” there is a real and difficult push for groups across the national network of water, justice, and river advocates to make. While Fitzgerald underscores the importance of this push, he also encourages us all to be realistic about finding the support you need. “We have to figure this stuff out together. That’s my main message to folks who are in my position working from a community based organization that’s trying to solve a really urgent issue: the urgency is real, and we need to push [for changes and equity], but it can sometimes be exhausting. Know that there are other folks out there doing that push, and there’s a community you can work with to do this.”

Fitzgerald also called on institutions like utilities and government agencies/offices to recognize community groups as partners in this push. “As partners there’s a certain level of respect and navigation of how we work together in a system that needs to happen, to make sure that we’re not looking back [on this moment] with the same questions the next time this kind of investment happens.”

How can you get involved to leverage this moment for your community’s water infrastructure and shifting out-of-date narratives? River Network has many different resources to meet you and your organization where you are, whether that’s joining the SRF Advocates Forum, exploring the SRF Advocacy Toolkit, working through our self-paced SRF Learning Series, or exploring our other federal funding resources.

The network, including the full MWC staff, will also be gathering for River Rally 2024 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in May 2024, where SRFs and other federal funding pathways will take center stage.

If you don’t work directly in water or advocacy, support River Network today, or find the local community groups in your area and support them with a donation to make this advocacy possible.

“I do really believe that collective action is going to lead to [equitable] solutions. To have a community of folks hearing that and thinking about how we work on it together is really special.”