Deep Dive: Environmental Justice

State-level environmental justice (EJ) policies continue to gain momentum while attempts to move federal legislation forward remains challenging, though the Biden Administration’s Justice40 initiative has reinvigorated conversations and actions related to environmental justice concerns. Historically, states first addressed EJ through executive orders or directives that lacked teeth, establishing advisory committees and taskforces or promising to increase public participation without enforceable measures. Some state environmental agencies developed internal equity plans or sought to integrate EJ in their decision-making and program design.

Environmental justice policies at the state level continue to move the needle on procedural, distributive, and corrective justice. Thanks to tireless advocacy from communities dealing with decades of environmental pollution, more state legislatures are considering environmental justice bills each year. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, in 2021 at least 150 bills related to environmental justice were considered across the country.

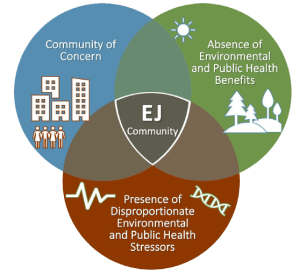

States that do have EJ advisory committees or task forces continue to advance core EJ principles through laws and regulations, including increasing public participation and community engagement in decision-making, developing methodology to identify and map communities that experience inequitable environmental burdens, defining “environmental justice” in law, requiring the consideration of cumulative impacts in permit decision-making, and allocating funding for EJ communities, especially related to climate justice and clean energy.

Lessons from New Jersey

New Jersey passed the strongest environmental justice law in the nation in 2020, becoming the first state to enable the state environmental agency to deny a permit for a facility that would cause adverse environmental or public health stressors on an overburdened community.

Key Policy Language

Direct language from New Jersey’s Environmental Justice law (S 232) articulates the duty of the state to ensure meaningful public participation in facility siting decisions and gives the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) the authority to deny permits if the approval of a permit will result in negative cumulative impacts in an overburdened community.

Introductory Language

“An Act concerning the disproportionate environmental and public health impacts of pollution on overburdened communities…”

“The Legislature finds and declares that all New Jersey residents, regardless of income, race, ethnicity, color, or national origin, have a right to live, work, and recreate in a clean and healthy environment ... The Legislature further finds and declares that no community should bear a disproportionate share of the adverse environmental and public health consequences that accompany the State’s economic growth; that the State’s overburdened communities must have a meaningful opportunity to participate in any decision to allow in such communities certain types of facilities which, by the nature of their activity, have the potential to increase environmental and public health stressors; and that it is in the public interest for the State, where appropriate, to limit the future placement and expansion of such facilities in overburdened communities.”

Source: NJ Department of Environmental Protection Office of Environmental Justice

Definitions

Environmental or public health stressors: “Sources of environmental pollution, including … concentrated areas of air pollution, mobile sources of air pollution, contaminated sites, transfer stations or other solid waste facilities, recycling facilities, scrap yards, and point-sources of water pollution including … water pollution from facilities or combined sewer overflows; or conditions that may cause potential public health impacts, including, but not limited to, asthma, cancer, elevated blood lead levels, cardiovascular disease, and developmental problems in the overburdened community.”

Facility: “(1) major source of air pollution; (2) resource recovery facility or incinerator; (3) sludge processing facility, combustor, or incinerator; (4) sewage treatment plant with a capacity of more than 50 million gallons per day; (5) transfer station or other solid waste facility, or recycling facility intending to receive at least 100 tons of recyclable material per day; (6) scrap metal facility; (7) landfill, including, but not limited to, a landfill that accepts ash, construction or demolition debris, or solid waste; or (8) medical waste incinerator.” Does not apply to medical waste incinerators that are attendant to a hospital or university and used for self-generated medical waste.

Low-income household: “A household that is at or below twice the poverty threshold as that threshold is determined annually by the United States Census Bureau.”

Overburdened community: “Any census block group, as determined in accordance with the most recent United States Census, in which: (1) at least 35 percent of the households qualify as low-income households; (2) at least 40 percent of the residents identify as minority or as members of a State recognized tribal community; or (3) at least 40 percent of the households have limited English proficiency.” (“Limited English proficiency” means that a household does not have an adult that speaks English “very well” according to the United States Census Bureau”).

Directives for the Department of Environmental Protection and Permit Applicants

The Department of Environmental Protection must make a publicly available list of overburdened communities within 120 days of the law’s passage, to be updated every 2 years.

“The department shall not consider complete for review any application for a permit for a new facility or for the expansion of an existing facility, or any application for the renewal of an existing facility’s major source permit, if the facility is located, or proposed to be located, in whole or in part, in an overburdened community, unless the permit applicant first:

(1) Prepares an environmental justice impact statement that assesses the potential environmental and public health stressors associated with the proposed new or expanded facility, or with the existing major source, as applicable, including any adverse environmental or public health stressors that cannot be avoided if the permit is granted, and the environmental or public health stressors already borne by the overburdened community as a result of existing conditions located in or affecting the overburdened community;

(2) Transmits the environmental justice impact statement … at least 60 days in advance of the public hearing required … to the department and to the governing body and the clerk of the municipality in which the overburdened community is located. Upon receipt, the department shall publish the environmental justice impact statement on its Internet website; and

(3) Organizes and conducts a public hearing in the overburdened community. The permit applicant shall publish a notice of the public hearing in at least two newspapers circulating within the overburdened community, including one local non-English language newspaper, if applicable, not less than 60 days prior to the public hearing. The permit applicant shall provide a copy of the notice to the department, and the department shall publish the notice on its Internet website and in the monthly bulletin … The notice of the public hearing shall provide the date, time, and location of the public hearing, a description of the proposed new or expanded facility or existing major source, as applicable, a map indicating the location of the facility, a brief summary of the environmental justice impact statement, information on how an interested person may review a copy of the complete environmental justice impact statement, an address for the submittal of written comments to the permit applicant, and any other information deemed appropriate by the department. At least 60 days prior to the public hearing, the permit applicant shall send a copy of the notice to the department and to the governing body and the clerk of the municipality in which the overburdened community is located. The applicant shall invite the municipality to participate in the public hearing. At the public hearing, the permit applicant shall provide clear, accurate, and complete information about the proposed new or expanded facility, or existing major source, as applicable, and the potential environmental and public health stressors associated with the facility.”

… “The department shall not issue a decision on an application for a permit for a new facility or for the expansion of an existing facility, or on an application for the renewal of an existing facility’s major source permit, if such facility is located, or proposed to be located, in whole or in part in an overburdened community until at least 45 days after the public hearing.”

Perhaps the most vital aspect of this law relates to the ability of the DEP to deny a permit if a facility creates negative cumulative impacts. Specifically, “The department shall, after review of the environmental justice impact statement prepared pursuant to paragraph (1) of subsection a. of this section and any other relevant information, including testimony and written comments received at the public hearing, deny a permit for a new facility upon a finding that approval of the permit, as proposed, would, together with other environmental or public health stressors affecting the overburdened community, cause or contribute to adverse cumulative environmental or public health stressors in the overburdened community that are higher than those borne by other communities within the State, county, or other geographic unit of analysis as determined by the department pursuant to rule, regulation, or guidance adopted or issued pursuant to section 5 of this act, except that where the department determines that a new facility will serve a compelling public interest in the community where it is to be located, the department may grant a permit that imposes conditions on the construction and operation of the facility to protect public health.”

Advocacy and Implementation Efforts in New Jersey

Long Road to Law

Institutionalizing matters of environmental justice began internally in New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) in 1998 through the creation of an Environmental Equity Task Force. Over the course of more than two decades, Governors reiterated the state’s obligation and duty to address EJ through executive orders. Governor Murphy signed Executive Order 23 in 2018. The Order directed DEP to facilitate an Environmental Justice Interagency Council (EJIC) to provide interagency collaboration related to agency action plans and ensure consistency in implementing EJ guidance. The EJIC meets and works with the DEP’s Environmental Justice Advisory Council (EJAC).

Environmental justice advocates that have served on EJAC maintained momentum and drove awareness of the need to address cumulative impacts over the course of several years. In 2009, a subcommittee of EJAC submitted a report to the Department of Environmental Protection, “Strategies for Addressing Cumulative Impacts in Environmental Justice Communities.” The report included recommendations for how to identify “hot spot areas”- vulnerable and burdened communities (what are increasingly referred to as “disadvantaged communities”)- and suggested that DEP reject permit applications in order to protect residents within hot spot neighborhoods. Eleven years later, this recommendation became law. Members of the statewide New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance (NJEJA) contributed to the report, and organized support for the environmental justice and cumulative impacts bill.

Key players from Ironbound Community Corporation, Clean Water Action of New Jersey, and other organizations demonstrated commitment to their communities over the long-term to get this bill over the finish line. State lawmakers introduced versions of this bill in previous years, but stories and research emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic helped the concept of cumulative impacts become tangible. Evidence that communities that endure more pollution are more vulnerable to other health issues, including Covid-19, bolstered support.

Organizers testified before committees, gathered a diverse group of supporters, and brought the Governor, mayors, and many state legislators on board.

Implementation on the Ground: Developing Regulations and Measuring Cumulative Impacts

In September 2021 DEP Commissioner Shawn LaTourette issued an Administrative Order to meet the legislative intent of New Jersey’s EJ law as a stop-gap measure while DEP promulgated regulations. As outlined in the law, DEP developed a list of overburdened communities.

In the spring of 2023, the final rule for the EJ law took effect. The rule outlines how permit applicants should prepare and submit an environmental justice impact statement (EJIS), implement public participation plans, and more.

In the future, EJIC may consider additional metrics related to defining overburdened communities and parameters for environmental and public health stressors and what types of goods and services may be attributable to policy or environmental decisions. DEP identified 31 stressors, including point sources of water pollution: surface water quality, combined sewer overflows, and all NJPDES sites. Drinking water quality (Number of Maximum Concentration Level (MCL), Treatment Technique (TT), and Action Level Exceedance (ALE) violations, and flooding are also water-related environmental and public health stressors that will be considered when developing EJ impact statements and approving or denying permits.

Lessons from New York

New York’s progress on environmental justice policies interlocks with the state’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). Political will supporting targeted funding to disadvantaged communities, considering cumulative impacts, and shifting decision-making processes continues to grow in recent legislative sessions.

Key Policy Language

In 2022, the New York Senate and Assembly passed S.8830 and A.2103C, outlining how the State’s Environmental Quality Review (SEQR) process considers cumulative impacts when reviewing permits in disadvantaged communities. Similar to New Jersey’s first-in-the-nation law, it requires the responsible permitting agency to consider whether a proposed action will cause or increase “a disproportionate or inequitable or both disproportionate and inequitable burden on a disadvantaged community that is directly or significantly indirectly affected by such action.”

The definition of “disadvantaged communities” was already articulated in the Environmental Conservation Law as “communities that bear burdens of negative public health effects, environmental pollution, impacts of climate change, and possess certain socioeconomic criteria, or comprise high-concentrations of low- and moderate- income households.”

The Environmental Conservation Law was amended to with a new section, including this language:

“When issuing a permit for any project that is not a minor project as defined in subdivision three of section 70-0105 of this article and that may directly or indirectly affect a disadvantaged community, the department shall prepare or cause to be prepared an existing burden report and shall consider such report in determining whether such project may cause or contribute to, either directly or indirectly, a disproportionate or inequitable or both disproportionate and inequitable pollution burden on a disadvantaged community. No permit shall be approved or renewed by the department if it may cause or contribute to, either directly or indirectly, a disproportionate or inequitable or both disproportionate and inequitable pollution burden on a disadvantaged community.”

Rules and Regulations

The Department of Environmental Conservation will adopt rules and regulations to administer this article, including “the form and content of an existing burden report which shall, at a minimum, include baseline monitoring data collected in the affected disadvantaged community within two years of the application for a permit or approval and shall identify:

(a) each existing pollution source or categories of sources affecting a disadvantaged community and the potential routes of human exposure to pollution from that source or categories of sources;

(b) ambient concentration of regulated air pollutants and regulated or unregulated toxic air pollutants; (c) traffic volume;

(d) noise and odor levels;

(e) exposure or potential exposure to lead paint;

(f) exposure to or potential exposure to contaminated drinking water supplies;

(g) proximity to solid or hazardous waste management facilities, wastewater treatment plants, hazardous waste sites, incinerators, recycling facilities, waste transfer facilities and petroleum or chemical manufacturing, storage, treatment or disposal facilities;

(h) the potential or documented cumulative human health effects of the foregoing pollution sources;

(i) the potential or projected contribution of the proposed action to existing pollution burdens in the community and potential health effects of such contribution, taking into account existing pollution burdens.”

Advocacy and Implementation Efforts

WE ACT for Environmental Justice, a long-time champion and agenda-setter of local, state, and federal environmental justice policies, advocated for this policy in partnership with other groups, including South Bronx Unite and the JustGreen Partnership (made up of dozens of partner organizations), as well as Environmental Advocates NY, Moms for a Nontoxic New York, Riverkeeper, New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, and Clean and Healthy New York. These groups led a virtual lobby day to discuss the importance of the bill with Assembly members and Senators and educated community members on the importance of cumulative impacts.

LJ Portis, the Environmental Policy and Advocacy Coordinator at WE ACT, reiterated the importance of building diverse coalitions to achieve policy wins. He says, “Given the intersectionality of environmental and climate work, to me it’s really important to make sure there are a variety of voices within a coalition. I think that’s really important to have representation of many perspectives within a sector. It’s great to have an environmental justice group, like WE ACT, be a part of something because that way we can lend our voice… making sure that there’s environmental justice in the work that’s being done. You want to have labor, you want to have racial justice, you want to have researchers, you want to have faith-based groups depending on the situation- you want to have a variety of perspectives.”

LJ Portis, the Environmental Policy and Advocacy Coordinator at WE ACT, reiterated the importance of building diverse coalitions to achieve policy wins. He says, “Given the intersectionality of environmental and climate work, to me it’s really important to make sure there are a variety of voices within a coalition. I think that’s really important to have representation of many perspectives within a sector. It’s great to have an environmental justice group, like WE ACT, be a part of something because that way we can lend our voice… making sure that there’s environmental justice in the work that’s being done. You want to have labor, you want to have racial justice, you want to have researchers, you want to have faith-based groups depending on the situation- you want to have a variety of perspectives.”

To learn more about New York’s climate and environmental justice laws, watch the State Policy Showcase featuring Anthony Rogers-White from New York Lawyers for the Public Interest.

The cumulative impacts law will take effect 180 days after passage- if you are a New Yorker keeping an eye on implementation, please let us know so we can provide updates in the future! The success of this law will be firmly connected to how the DEC’s rules and regulations will identify pollution burdens.