State Policy Approaches to Floodplain Restoration and Protection

What’s the Issue?

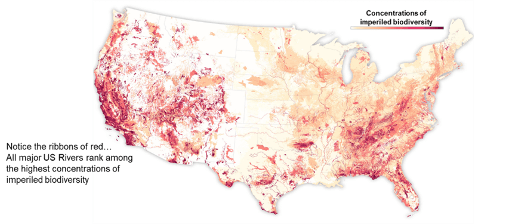

Over the past thirty years, the science guiding how we manage our rivers has been evolving to emphasize the river as a whole system. Past approaches prioritized constraining the river into a stable and predictable channel to control the delivery of water downstream and reduce chances of the river overflowing its banks and flooding adjacent communities. This approach has devastated river health and degraded the multitude of essential ecosystem benefits that sustain our communities, economies, and the environment.

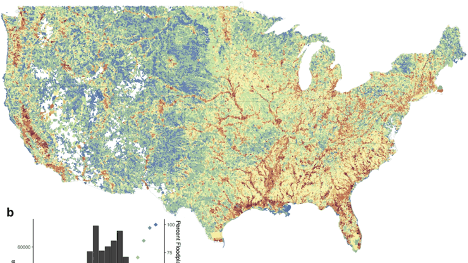

Flooding is a natural occurrence, and most rivers and streams, when allowed to function without human encroachment, will seasonally overtop their banks, distributing nutrients and sediment across the floodplain, shifting their channels, and recharging groundwater. However, human activities along, within, and across our nation’s rivers have constrained those natural functions.

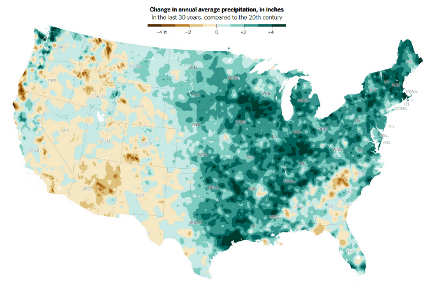

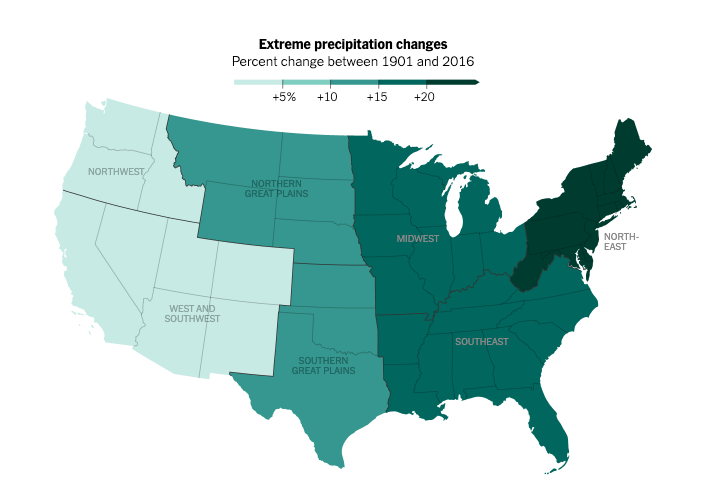

The impact of floods on communities has increased as we have encroached on the space that rivers require to overtop their banks, shift course, and recharge riparian lands. Increased amount, frequency, and intensity of precipitation in much of the country and increased frequency and intensity of storms associated with climate change have and will continue to lead to flooding that has devastating impacts on communities, water-dependent species, infrastructure, and often involves loss of life.

Many states and local governments, and some Tribal governments, have developed programs and regulations to limit what structures and activities are allowed in the floodplain. Those regulations are usually tied to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and emergency management agency guidelines associated with federal or state flood insurance and assistance. The “management” of the floodplain has been driven by the desire to avoid costly damage to human life or physical property through hazard mitigation rather than holistic floodplain management approaches.

An emerging tool in the resiliency adaptation toolbox aligns the management of water resources, land use changes, and potential hazards to improve benefits for communities and the environment in an equitable manner. There are many names for this new paradigm—nature based solutions, integrated river basin management, integrated floodplain management (IFM), and more—but the underlying tenet is the same. Rivers need adequate space for the natural processes that create the multiple benefits our communities, economies, and the environment rely upon to be healthy and resilient.

To maintain a healthy, functioning river requires managing the entire river corridor—the river channel, all of the floodplain, the riparian areas and wetlands, and the connected aquifer—as a single interdependent system. Rather than trying to change the way the river behaves, various IFM models acknowledge that river systems are dynamic and require space within the river corridor for the natural processes including high and low flows, flood water storage in adjacent floodplains, and sediment deposition and transport.

Below, we take a closer look at examples from Washington and Vermont where those states have developed IFM programs that help break down the silos across entities involved in protection and restoration of rivers and floodplains and adjacent communities.

Examples of State Policy and Lessons from the Network

Vermont

Washington

Additional Resources

- Association of State Floodplain Managers State and Local Floodplain Management Program Assessments

- Integrated Watershed Management – Association of State Floodplain Managers and National Association of Wetland Managers partnership with EPA for training on integration of Clean Water Act Programs, natural hazard mitigation planning, and implementation to reduce flood risk and improve water quality

- The Power of the Watershed Approach for Floodplain Management

- Carson River Watershed Regional Floodplain Management Plan 2008

- How Nature is Taming Policy: A Watershed Approach to Flood Risk Management

- State Policy Showcase: Approaches to Floodplain Restoration & Protection

Development of the State Policy Approaches to Floodplain Restoration and Protection State Policy Hub category was led by

Gayle Killam with Water Policy Pathways

Floodplain Restoration & Protection Policy Database

Our friends at American Rivers are developing their 50 State Floodplain Strategy as well. We will include additional information here as it becomes available.

| Name | State | Action Agency | Policy Focus | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Act 250 | Vermont | Natural Resources Board | Act 250 is Vermont’s land use and development law. Projects that require an Act 250 permit and are located within a flood hazard area or river corridor must meet requirements under Criterion 1D–Flood Hazard Areas, River Corridors. |

|

| Act 121 | Vermont | Department of Environmental Conservation, in consultation with the Agency of Commerce and Community | Act 121 authorizes statewide river corridor regulation and the municipal adoption of higher state floodplain standards. |

|

| Vermont Flood Hazard Area and River Corridor Rule | Vermont | Department of Environmental Conservation | The Flood Hazard Area and River Corridor Rule regulates development exempt from municipal regulation within designated Flood Hazard Areas and River Corridors. |

|

| River Corridor & Floodplain Protection Program | Vermont | Department of Environmental Conservation | The River Corridor & Floodplain Protection section works with landowners, municipalities, regional planning commissions, NGOs, and agencies of state and federal government to reduce flood risk by protecting and restoring natural and beneficial river and floodplain functions. |

|

| Climate Commitment Act | Washington | State of Washington Department of Ecology | The Climate Commitment Act (CCA) caps and reduces greenhouse gas emissions from Washington’s largest emitting sources and industries. A portion of funds can then be used for clean water investments and restoration of natural floodplain ecological function. |

|

| The 310 Law / The Natural Streambed and Land Preservation Act | Montana | Montana's Conservation Districts | The purpose of the 310 law is to keep rivers and streams in as natural or existing condition as possible, to minimize sedimentation and to recognize beneficial uses. Any individual or corporation proposing construction in a perennial stream must apply for a 310 permit through the local conservation district. |